Exhibition

Tender

Curious Works

About the exhibition

Mohammad Awad, Sharon Mani, Diamond Tat and Carielyn Tunion

If tenderness doesn’t come to mind when you think of Western Sydney, then you don’t truly know it.

Tender reveals the nuances and tender sides of the communities of Western Sydney through four individual but interconnected documentary films by multidisciplinary artists: Mohammad Awad (3awadi), Carielyn Tunion, Diamond Tat, and Sharon Mani.

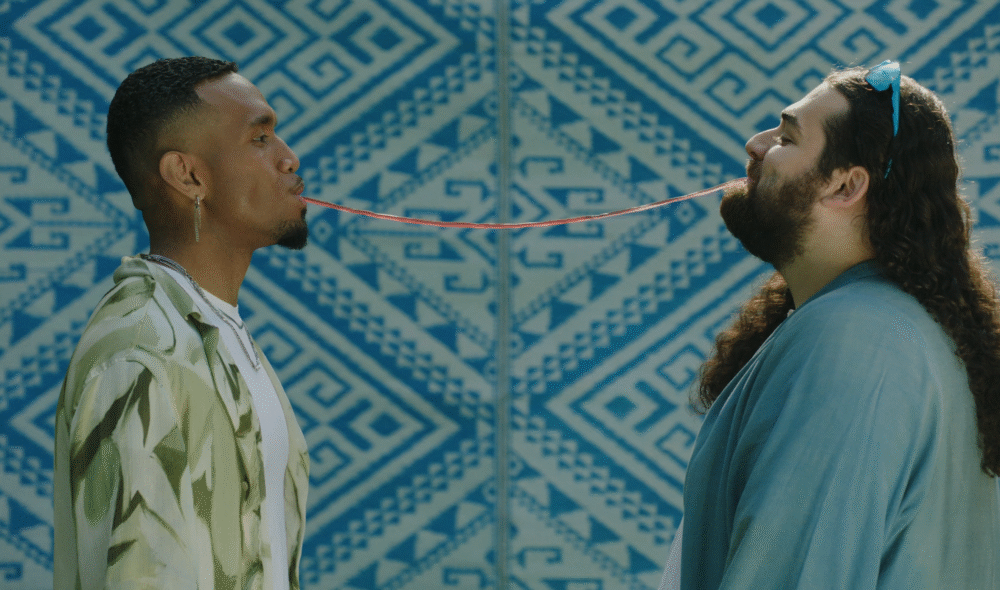

Mohammad Awad debunks the myth that queer and trans people need to leave their Western Sydney homes to find love, joy and intimacy, in Bikes, a documentary music video.

Carielyn Tunion’s video poem, i am a deepsea fisherwoman, but i do not catch fish, explores the diaphanous connections of a personal diasporic family story rooted in the archipelago known as ‘the Philippines’ and Hong Kong.

Diamond Tat’s poetic documentary film, Marrow, is a cinematic ode to womanhood inspired by her and her mother’s immigration experience, capturing both its silent volatility and profound gentleness.

And in Sharon Mani’s work, At The Heart of it, local memories and stories are shared from those who call Western Sydney home.

Each of these films welcomes viewers into an intimate exchange of personal narratives, revealing the tenderness in our communities and experiences that is often overlooked by mainstream media. We want those who recognise themselves in these films to feel comfort, joy, and validation; and for those who don’t, to see us for who we are.

These work were commissioned by Sydney Opera House and produced by Curious Works, under the creative and technical direction of Elias Nohra. The project was supported by the NSW Government through Create NSW.

Nexus Arts Gallery

27 November 2025 – 16 January 2026

Explore the exhibition

-

- Artwork Marrow (still)

- Artist Diamond Tat

- Year 2024

- Medium Video

-

- Artwork At the Heart of it

- Artist Sharon Mani

- Year 2024

- Medium Video Documentary

-

- Artwork i am a deepsea fisherwoman, but i do not catch fish

- Artist Carielyn Tunion

- Year 2024

- Medium Video

-

- Artwork Bikes

- Artist Mohammad Awad

- Year 2024

- Medium Video / Music Video

Catalogue essay

Ribs

Our hearts yearn for homes

In school, we were tasked with building a city through a computer software program. We had to give it a portmanteau of our first and last names and ensure residents paid taxes, their government wasn’t corrupt and that there wasn’t too much crossing of imaginary boundaries (immigration, hedonism, public acts of affection). My city had sleek skyscrapers and a metro station with one line (blue from A to B). One couldn’t cross B to A, nor dream about stopping too long at both. When I presented it in class, I was queried as to why there were no neighbourhoods. Pockets of air, a set of lungs exhaling music, laughter, sadness, grief etc. My teacher said my city was a pair of ribs containing no breath. She told me to re-plan it again and think about where I grew up.

*

I always chase love to where it resides

The cracked snake skin of bitumen cut through the hill like arteries. The zig zag journey made me car sick as we barrelled up the freeway leaving a trail of smoke and tyre marks behind us. Their house was a Jenga block interconnected with others wearing pale yellow bricks and ivy and muck and rust and ghosts. Vines wrapped like fingers, a tree in stubborn decay. From the outside – it looks like a tomb – unloved and scorned by the sun. When we open the heavy mahogany door – a burst of light warms us. It is a metaphysical reaction to arriving – and I never know whether I am making it up or if my brain is playing a trick – like when taking a phantom stair or feeling a jolt when falling asleep. I know one day I will grieve this place and I forget to drink in what’s left.

My grandparents have lived in this neighbourhood since arriving in Australia – and it is remarkably the same – frozen in a glaze of working class cringe. Christmas lights in February, the milk man who no longer comes still delivers his neighbours milk, an ice cream truck is melting on its way to the deli that sells 50 cent bread rolls, the same SUV squeals down the drive into a tin garage. Poh Poh takes me to the park and I look at the other children with their grandparents who won’t be here forever. She tells me she loves me – but then asks me to say it back – over and over again as if she didn’t hear it enough when she was young. She holds us all in her ribs – each exhale into the itchy afternoon air painful and alive – a reminder of why she is alive.

*

An oliver makes three sticks burning in the wind

When they were looking for a house in the suburbs their family said stay away from this suburb because it was akin to farmland and Gong Gong left China to escape farming and jail, of which he had escaped three times. They wanted to contain immigrants into faraway pockets so that they didn’t have to look at them. Tucked away in these corners, the new Australia buried tokens of home in the thirsty soil waiting for them to bloom. They weregiven a mound of dirt of which they didn’t anticipate to sprout roots in splendid tears of rain. In Sydney, new suburbs propped up like protest, interconnecting communities and joy in a raucous act of rebellion. Here, community pulses through a rumpus room became a mahjong den, a coffee shop where no one speaks English, a barbeque pit becomes bowed in prayer. Each afternoon, Poh Poh kneeled on the hard concrete and waited for God. From the outside, they saw fear, but she was at peace. The scent of joss and grief perfumed the gums and damp clouds.

*

Don’t tell me love does not exist here simply because you can’t see him

Gong Gong takes his last breath emancipated from his body. When he reaches heaven, he doesn’t think of this hospital bed or this torso ripped apart with disease or this air that he can no longer swallow. He is on his feet following the street signs where he is greeted by the shadows who no longer reside. The cheap butcher that sells the off cuts gives him his favourite Vienna sausages wrapped in newspaper. The coin activated ride outside of Bi-Lo is stuck in seesaw rhythm. He picks up an inky grocery catalogue in Cantonese that will later be used as a bin liner. His favourite shop is shutting down soon to make way for a carpark. He buys one last custard tart – the one he could never find in the city – it melts like gold. Dying came like peace – seeing me – and the road stained on the back of my feet waiting in staggered anticipation of one last day of summer holidays – his breath burning away like prayer.

*

The latte line kind of divides us

When I am old enough to consider property – not in a computer game – the realtor says to stay away from the boundary that divides the city from progress to decay. She says that when there is a prevalence of cultural communities in one space there is no containment. I drive up the hill, tracing my steps, back to where I can breathe again. Watching community unfurl on the cricket ground, joy breaks through the morning, in laughter, and brazen provocations of belonging. Without us, this city would be an empty set of ribs, gasping and strangulated in empty sighs. I am reminded of the intimacies my ghosts left behind – a crack in the pavement, an inky finger print on a map that would always lead back here. That our boundaries were never meant to separate us. To feel joy is to breathe it, to un-contain it, to see it with eyes open.

Olivia De Zilva

2025