Exhibition

混沌知觉 Chaostopia

Alice Hu

About the exhibition

By Alice Hu

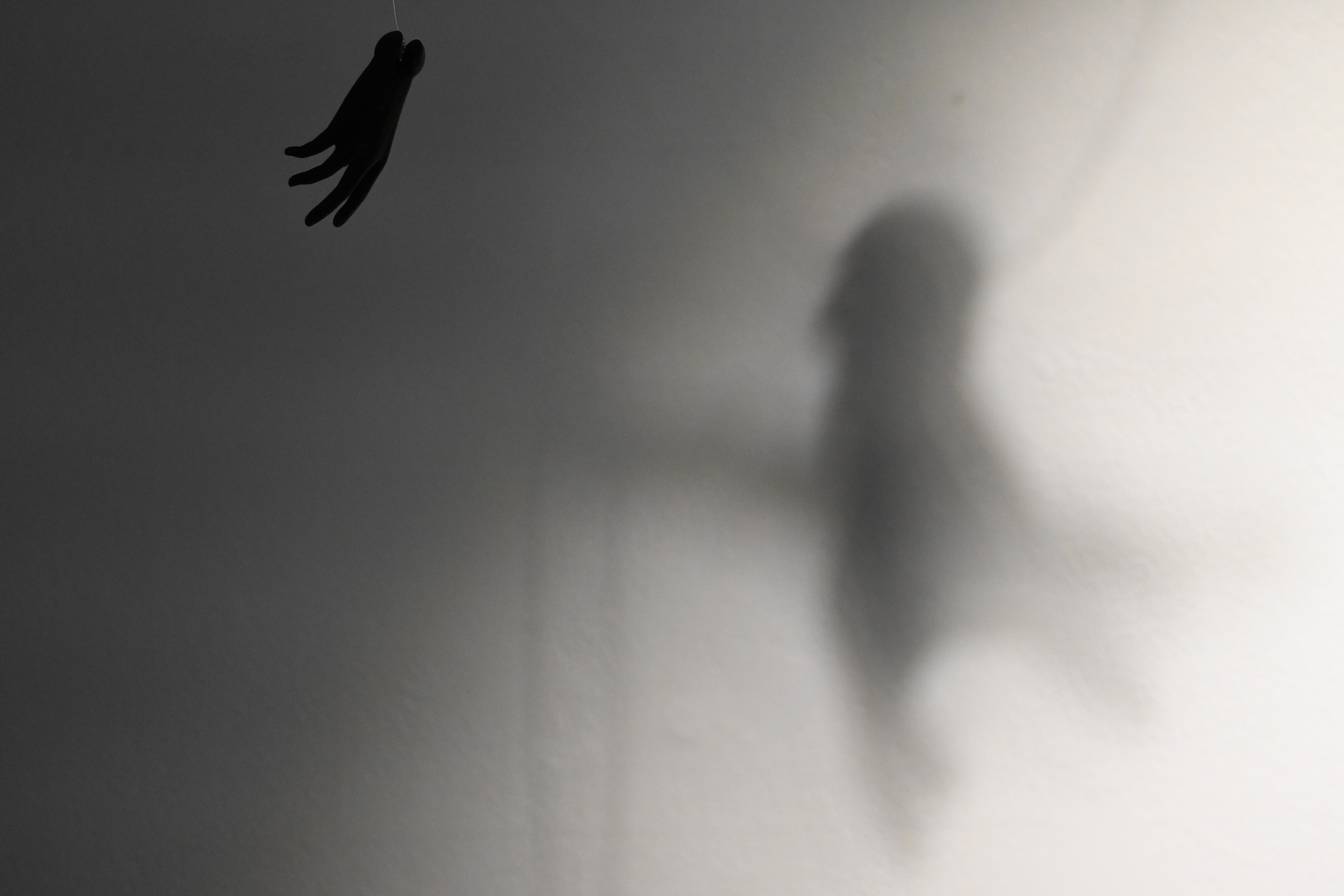

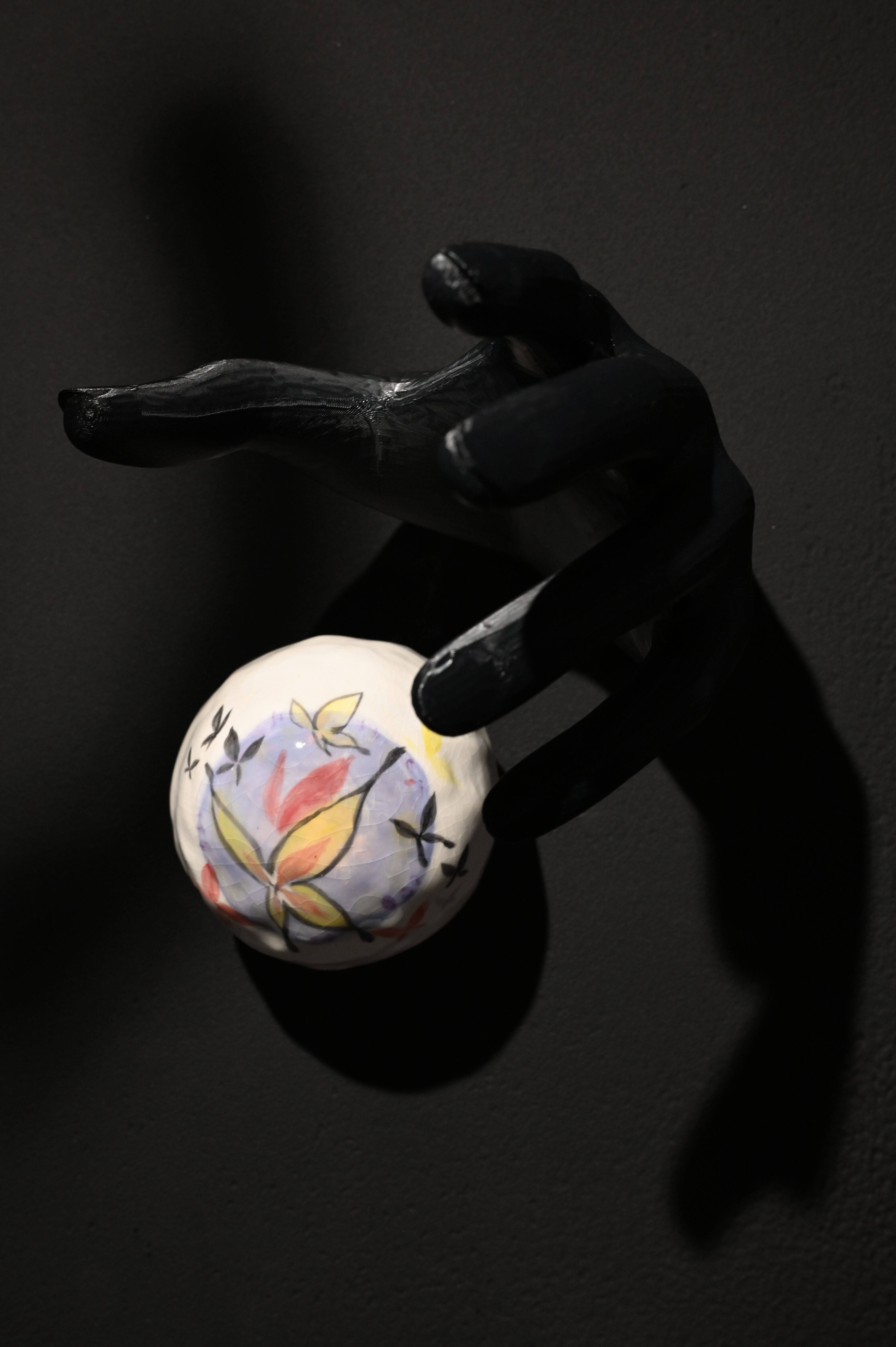

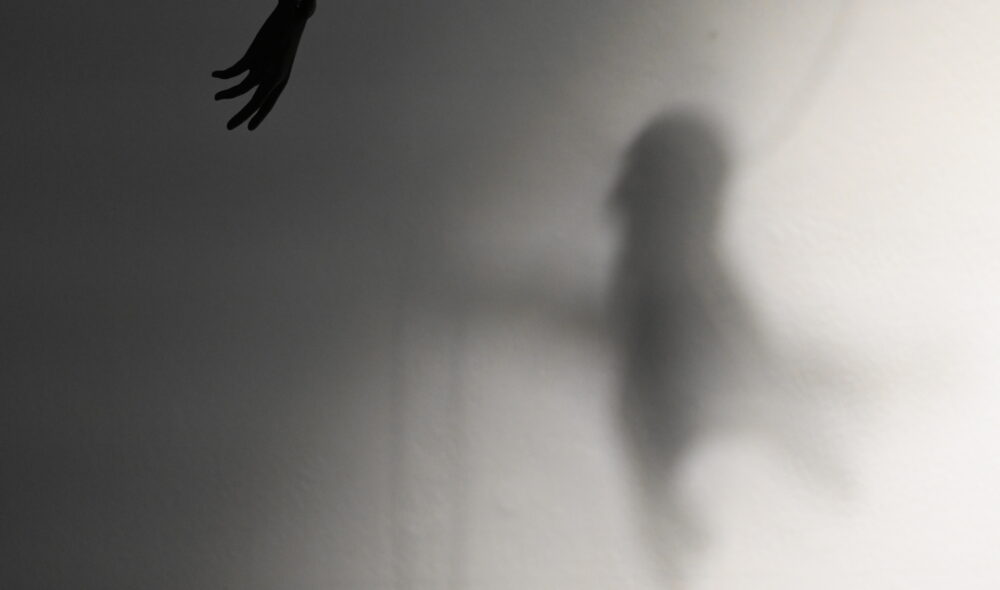

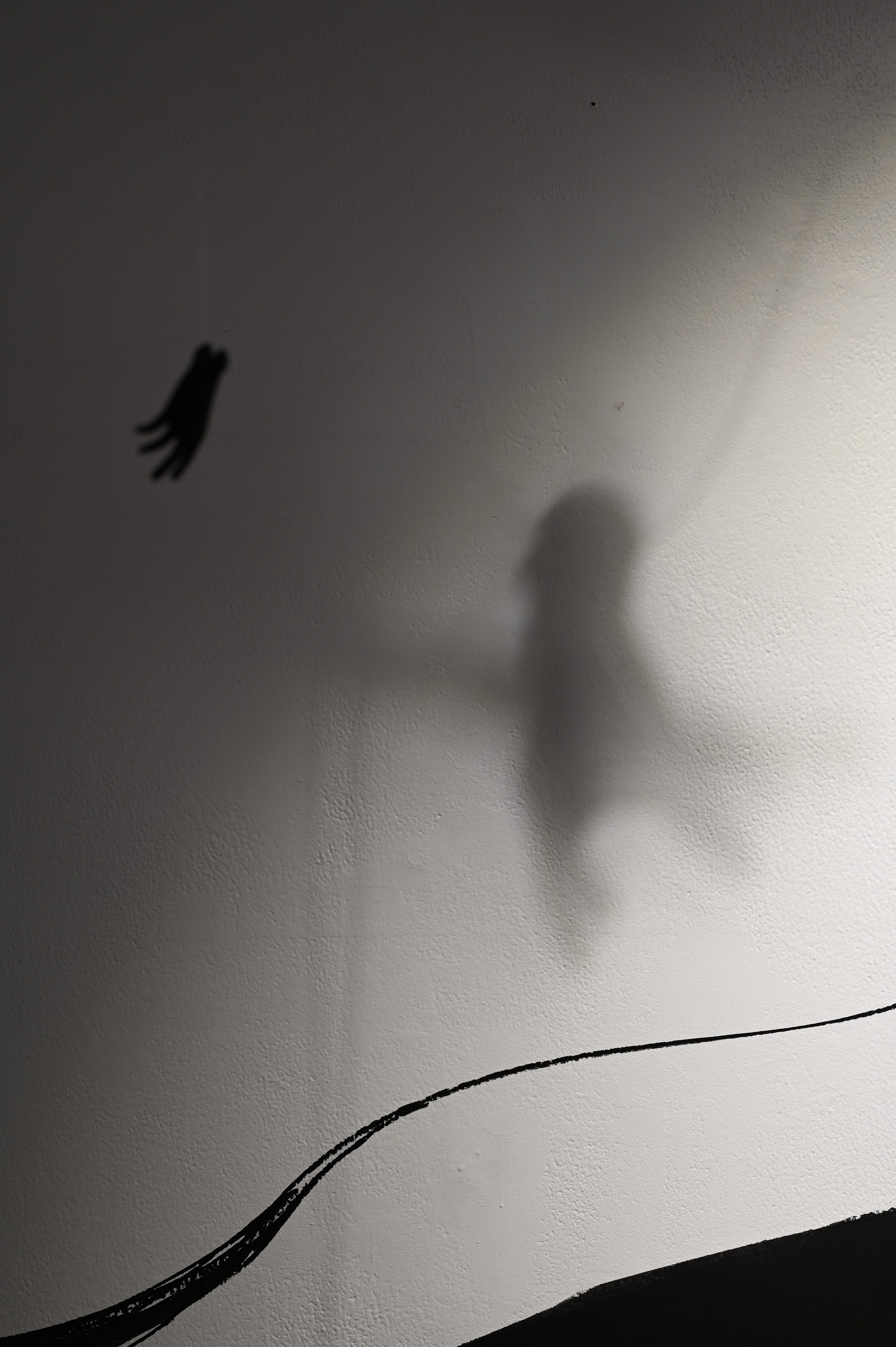

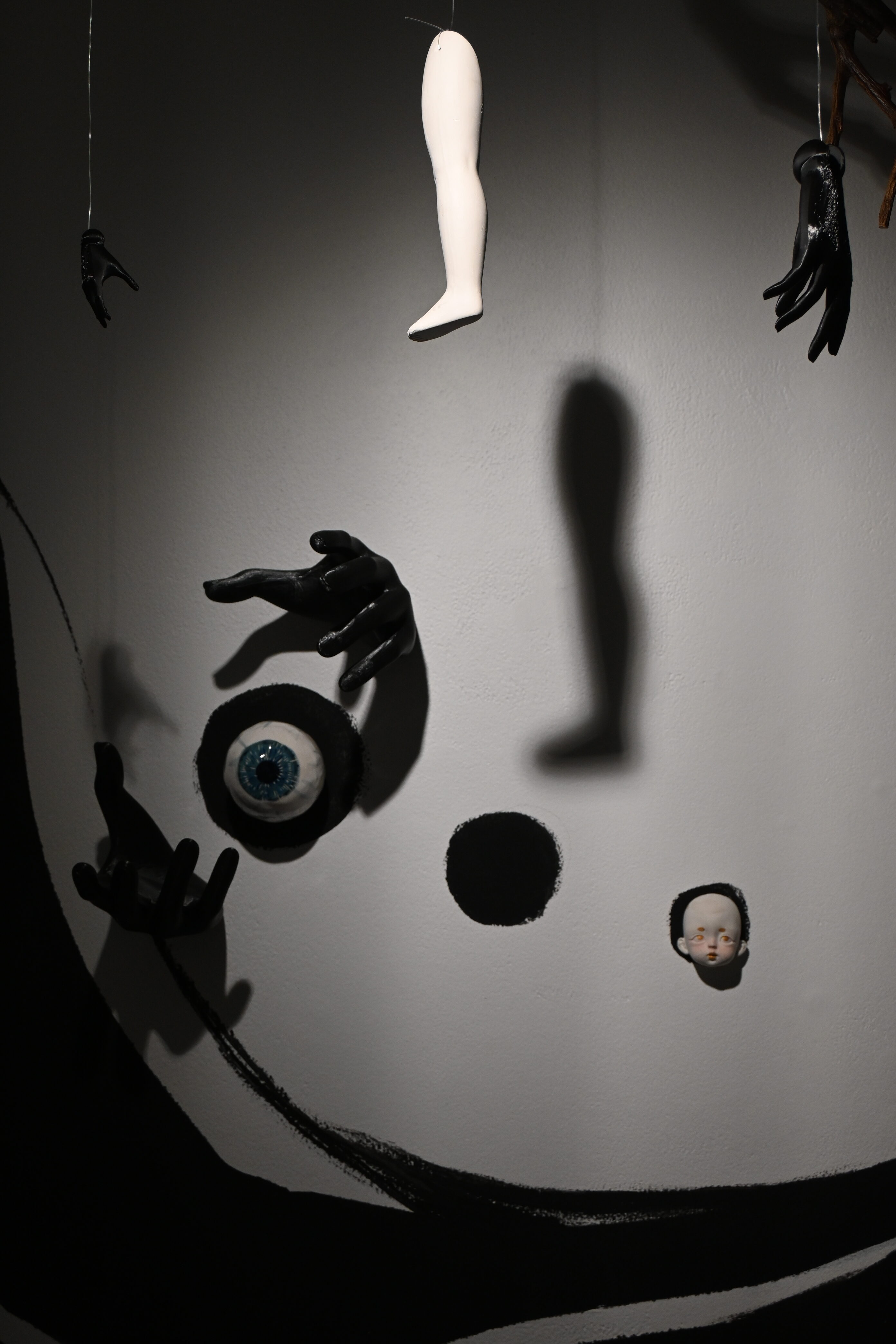

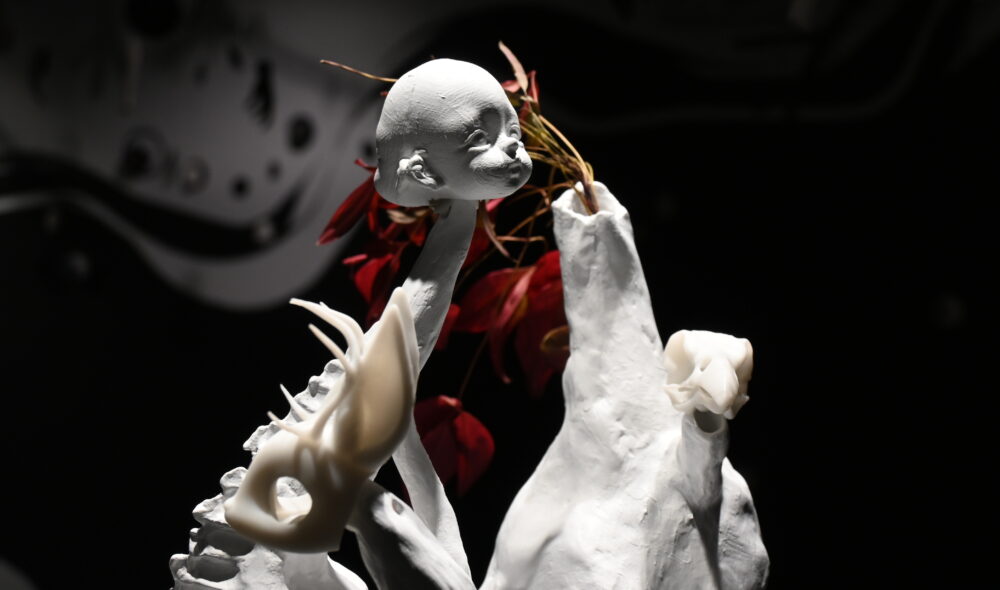

In Chaostopia, tree branches gathered from around Tarntanya fill the gallery, splaying downwards from the ceiling, protruding from walls, suspended across the space, floating. The gallery walls are painted black, suggesting a cosmic state of being, while eyes, hands, and other corporeal objects intertwine with the branches.

Hundun, is a state of ‘deep chaos’; an embryonic condition that is placed at the root of creation; a primordial state of ‘nothingness’ that is pregnant with endless possibility, where form and matter are undifferentiated yet teeming with energy. The Chinese word defies direct English translation and can be linked to Taoist cosmology, which understands the universe as cyclic, following infinite, self-sustaining cycles, and containing various energies that affect each other in complex patterns. As Alice describes it, chaos is formless matter that compels and conjures intricacy, a sponta- neity that nevertheless comprises a sense of order. The overarching impression of Chaostopia is one of entanglement; a site where categories blur and margins melt, a site where the self is extended through its relation with others.

Video by Yusuf Ali Hayat

Explore the exhibition

-

- Artwork 混沌知觉 Chaostopia

- Artist Alice Hu

- Year 2024

-

- Artwork 混沌知觉 Chaostopia

- Artist Alice Hu

- Year 2024

-

- Artwork 混沌知觉 Chaostopia

- Artist Alice Hu

- Year 2024

-

- Artwork 混沌知觉 Chaostopia

- Artist Alice Hu

- Year 2024

-

- Artwork 混沌知觉 Chaostopia

- Artist Alice Hu

- Year 2024

-

- Artwork 混沌知觉 Chaostopia

- Artist Alice Hu

- Year 2024

-

- Artwork 混沌知觉 Chaostopia

- Artist Alice Hu

- Year 2024

-

- Artwork 混沌知觉 Chaostopia

- Artist Alice Hu

- Year 2024

-

- Artwork 混沌知觉 Chaostopia

- Artist Alice Hu

- Year 2024

-

- Artwork 混沌知觉 Chaostopia

- Artist Alice Hu

- Year 2024

-

- Artwork 混沌知觉 Chaostopia

- Artist Alice Hu

- Year 2024

-

- Artwork 混沌知觉 Chaostopia

- Artist Alice Hu

- Year 2024

-

- Artwork 混沌知觉 Chaostopia

- Artist Alice Hu

- Year 2024

-

- Artwork 混沌知觉 Chaostopia

- Artist Alice Hu

- Year 2024

-

- Artwork 混沌知觉 Chaostopia

- Artist Alice Hu

- Year 2024

-

- Artwork 混沌知觉 Chaostopia

- Artist Alice Hu

- Year 2024

-

- Artwork 混沌知觉 Chaostopia

- Artist Alice Hu

- Year 2024

-

- Artwork 混沌知觉 Chaostopia

- Artist Alice Hu

- Year 2024

-

- Artwork 混沌知觉 Chaostopia

- Artist Alice Hu

- Year 2024

-

- Artwork 混沌知觉 Chaostopia

- Artist Alice Hu

- Year 2024

-

- Artwork 混沌知觉 Chaostopia

- Artist Alice Hu

- Year 2024

Catalogue essay

Fractals abound in nature: they’re present everywhere, from clouds to coastlines, mountains to galaxies. These self-similar, recursive patterns generate themselves across scale, so that one part resembles the whole, and one form implicitly contains the history of all such forms.[1] There is elegance in their repetition and symmetry, and beauty in the tension held between method and accident. Fractal patterns often result in arterial or venous structures – which is to say, branching is the most common path nature follows.

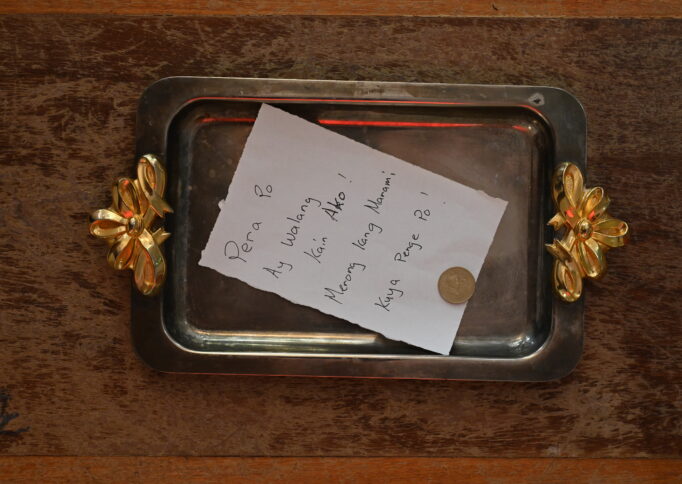

In Alice Hu’s exhibition Chaostopia, tree branches – gathered from around Tarntanya – fill the gallery, splaying downwards from the ceiling, protruding from walls, suspended across space, floating. The gallery walls are painted black, suggesting a cosmic state of being, while eyes, hands, and other corporeal objects intertwine with the branches. This mingling of sensorial motifs – the haptic function of hands, the visual faculty –speaks to the multitude of ways we are attached to, and process, the world, and hints at the impossibility of removing ourselves from the sensations (and affective states) that circulate around us. “We do not own anything, even the most intimate components of ourselves,” Alice Hu said to me. “Everything we do and know, we must learn first.” Walking into the gallery, one experiences the collective intelligence implied by Alice Hu’s statement; the exhibition feels like a representation of the individual accretion of knowledge, emotion, and perception that is inevitably a communal project.

Alice Hu is drawn to the Chinese word hundun, a term that defies direct English translation. It is a state of ‘deep chaos,’ an embryonic condition that brims with potential and bristles with futures. Hundun can be linked to Taoist cosmology, which understands the universe as cyclic, following infinite, self-sustaining cycles, and containing various energies that affect each other in complex patterns. Hundun (‘chaos’) is placed at the root of creation, expressing the primordial state of ‘nothingness’ that is pregnant with endless possibility, where form and matter are undifferentiated yet teeming with energy. As Alice Hu describes it, chaos is formless matter that compels and conjures intricacy, a spontaneity that nevertheless comprises a sense of order.

Like the tree branches that manifest across the gallery, the eyes are also constituted by fractal branching: a replicating, cascading pattern spans every retina; such is the ubiquity of fractals. Though they have been observed and studied throughout history, the mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot first named the term in the 1970s, and his work transformed the field of geometry by demonstrating that the complex and intricate patterns pervading our natural world could be reached via fractal sets. As fractal geometry expanded, the ‘chaos game’ was developed. The ‘chaos game’ is an iterative function system – i.e. a type of algorithm – that yields natural forms.[2] One popular example is the Barnsley fern: the algorithm involves four linear contractions applied iteratively to a square, resulting in transformations that mimic a fern-like structure. Which is to say, plug this algorithm into the computer and you will see a fern materialise on screen. In the words of Valentine in Tom Stoppard’s Arcadia, “the unpredictable and the predetermined unfold together to make everything the way it is. It’s how nature creates itself, on every scale, the snowflake and the snowstorm.”[3] I find that there is something of the fractal in the concept of hundun, that is, both are frameworks to describe the generative potential of randomness and transformation. Both concepts articulate the beauty and complexity inherent in the production and reproduction of our worlds.

Upon entering Alice Hu’s Chaostopia, the overarching impression is one of entanglement. It is a site where categories blur and margins melt, a site where the self is extended through its relation with others. The feeling of relation Chaostopia inspires is reminiscent of what Edouard Glissant terms ‘toute-monde:’ an exchange that respects complexity and plurality, that does not seek to totalise but rather gathers difference. In this way, Alice Hu renders the gallery a thirdspace[4]: the gallery is a counter-site, an ‘enacted space of utopia’ in which the world is both represented and contested. Chaostopia transcends binary oppositions between material and psychic realms, allowing us to see and to feel the intricate interplays between order, disorder, spontaneity, and transformation.

[1] P. Prusinkiewicz and A. Lindenmayer, The Algorithmic Beauty of Plants, Springer-Verlag, New York, 1990

[2] D. Gulick and J. Scott, The Beauty of Fractals: Six Different Views, The Mathematical Association of America, USA, 2010

[3] Ibid

[4] See E. Soja, Thirdspace, Blackwell Publishers Inc, Massachusetts, 1996

Alice and Adam Hu in Conversation

Video by Yusuf Ali Hayat

Meet the artists & curators

I am an emerging artist who has the eager to seek achievements in my practice and build milestones in my professional pathway. My works are often inspired by my multicultural background, the idea of acculturation and my unique aesthetic from personal experience.

I work with multiple medium such ceramics, paintings and installation, as a contemporary artist the medium should not limit my idea but to improve it. I have been working a lot with ceramics at this stage as it has a strong bond with me and my birth country, mythologies stories I grow up listening to, and a unique material that could combine what I’ve experienced in Australia, a material of multicultural with many possibilities.